The first week of March saw the most anticipated annual event in the blue economy, or the “Davos of the oceans” as some call it. Initiated by The Economist magazine, the 9th edition of the World Ocean Summit Virtual Week brings together the cream of the crop in the field of ocean strategies.

The United Nations, the EU, powerful environmental NGOs, institutional investors including investment funds and banks, university applied research centres and consultancies close the gap. They all come to listen to the familiar chorus of grievances from government speeches, especially from the small and vulnerable states of the South. All then agree that the only way to save the planet and stem the loss of marine biodiversity is to fund conservation.

Funding conservation or keeping the funding?

Debt swaps, blue bonds, insurance policies for marine ecosystems or the creation of trust funds, financial instruments are becoming increasingly innovative and inclusive. The approach is no longer that of development aid. Conservation funding is now multi-stakeholder and the beneficiary State is a direct collaborator, even if it may be a sword of Damocles. The idea is that the funds available to the state for biodiversity protection are not sufficient, a truism given that the state in question is both burdened with debt and on the front line of the climate crisis. It is then approached by intergovernmental or non-governmental organisations that come to explain, with flashy presentations and solid feedback, why it is in its interest to enhance the conservation of its marine resources (worth several million dollars) and how it can convert its liabilities into a financial asset capable of attracting private investment (“eco-investment”). The beneficiary state then sets in motion the incentive measures and consequently undertakes to modify its regulations to facilitate the flow of capital. This dynamic, justified in the name of the blue economy, translates in practice into a subjection of the State, which then finds itself dispossessed of its sovereign rights over its maritime spaces.

From the blue economy to “blue colonialism”

The subjection here is economic. In practice, it leads to the private management of public spaces, spaces that the international law of the sea subjects to the jurisdiction of the coastal State and in which the latter exercises its economic, exclusive, “finalised” rights. But the argument that the State in question is not capable of properly managing its own spaces is reminiscent of the justifications for colonisation in the past, which were purely state or geopolitical*.

An instrumentalisation of environmental protection and conservation that is deliberate, but consented to. The State is moreover encouraged to diversify its traditional maritime sector or to multiply the uses of the sea in space and time in order to favour the potential of shared economic development. Maritime spatial planning” (or MSP, as it is commonly known) is strongly recommended. A corollary of the blue economy and the result of a European directive, MSP promises nothing less than a reduction in conflicts of use, transparency in the visibility of space allocation and the legal guarantee essential for investments. However, by prioritising certain activities over others, does this not exclude uses and users who enjoy the same rights over these spaces, and therefore precisely to appropriate these spaces? The question would not arise in the same terms if the manager were the State. However, most of the time, the intergovernmental or non-governmental organisation that has come to an agreement with the State has taken care to transfer competences in the field of maritime space management to an entity that is legally linked to it, and often for an indefinite period.

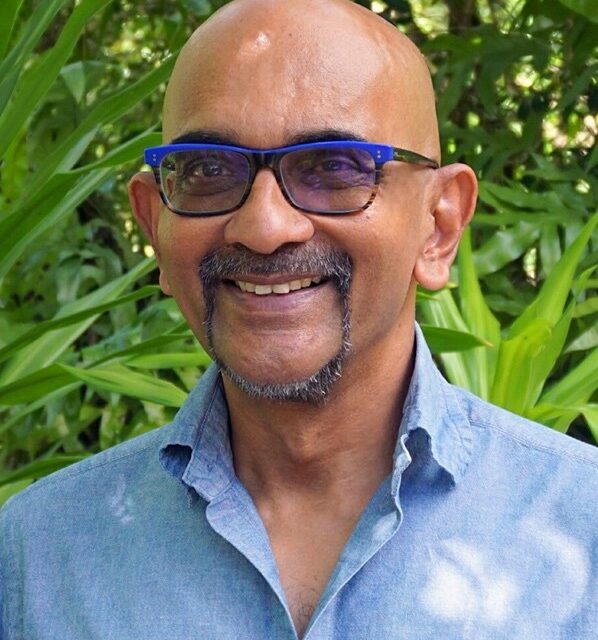

Special maritime spatial planning in the Seychelles

The privatisation of maritime spaces in Seychelles is not new. Certain entire islands have long had private owners and the first maritime concessions dating from the colonial era, whether for dyking or land (and sea) development, still exist legally today. Thus, the tourist activity generated by the seashores and lagoons is a legitimate translation of what the sovereign State allows to happen “at home”. However, in recent years, this freedom of action has been transformed into pressure, directly experienced by the State, from the American NGO The Nature Conservancy, to which it has contracted a blue loan for the conservation of its marine areas. The Seychelles’ Conservation and Climate Adaptation Trust (SeyCCAT) was created to receive the funds linked to this loan (or blue bond). In practice, this entity must control the planning of maritime areas, both in fact and in law, with the objective of achieving and maintaining the conservation of 30% of the Seychelles’ marine areas, which is achieved precisely through the creation of marine protected areas. Half of these marine protected areas currently have “no-take” status, which is the most comprehensive legal protection, but which in fact translates into a total ban on fishing activities, which the NGO considers too “destructive”. Oil drilling would apparently be less destructive, given the recent allocation of a space dedicated to oil extraction activities, which did not fail to raise an outcry. For specialist Dr Nirmal Jivan Shah, founder and president of the NGO Nature Seychelles, it is not surprising to see such an aberration in terms of environmental ethics. He calls the bond a ‘blue grab’ for resource grabbing, but justified by the MSP. “The problem is that with MSP, no one sees the need to critically re-examine, and if necessary reform, governance at national level. MSP is in itself a very good tool for spatial planning, except when it comes to ‘sealing’ and reinforcing the status quo and the business as usual scenario in terms of who owns what and who does what. Thus, the Seychelles model, which has led to the financialisation of maritime spaces in the name of conservation, is emblematic of a win-win partnership of interests, the losers of which are undoubtedly the Seychellois themselves.